Fact-Checking and Verification

Fact-Checking

Fact checks can unconsciously spread myths and false narratives if you don’t structure your debunking well enough. By using the same language, stories and images, you might give a false narrative more notoriety and create more familiarity.

- Don’t link to places where people can find more about the narrative or myth.

- Warn people about the sections where you describe false information, point out that it is false.

- Don’t use the same content (images, videos, etc.) as the original piece.

- Don’t just point out the flaws in a false story, but also include a real alternative and link to factual articles.

- Focus on smaller elements of a false story and explain why it is incorrect. Don’t use the entire narrative or myth to give more context.

- Don’t debunk stories that have not seen much engagement. We don’t want to give it more attention if it’s still a niche story.

- But also, don’t debunk too late. We don’t want falsehoods to gain momentum.

There are two questions you should ask yourself after you have done a fact checking exercise.

- What does the audience believe when spreading this information?

- What is the underlying emotion in the audience who are sharing and spreading this information?

Once you have done a fact check, found that the information is false, the starting point of your article or piece should be what your audience currently believe and then present them with the new information in a way that considers their logic.

How to Spot Fake or Unreliable Scientific Claims During COVID-19

Throughout the current epidemic, new scientific claims are appearing on a daily basis. It is important to evaluate these claims in order to weed out the true scientific facts from pseudoscience. Many published articles have not been fact checked or peer reviewed, therefore it is up to journalists to recognise bad science reporting. Following these points will help you in doing so.

- Clickbait headlines: As headlines are designed to tempt readers into clicking on them, scientific research can often be simplified and potentially even misrepresented.

- Conflicts of interest: Companies may be hiring scientists to publish research that is specifically beneficial to them, often for personal or financial gain.

- Correlation and causation: There is no proven correlation between 5G and COVID-19, despite the virus beginning in Wuhan, where 5G was being tested. Be wary of other conspiracies such as this that confuse correlation and causation.

- Issues with samples and test size: Small sample sizes or unrepresentative samples, and no control group or blind test can provide problematic results in trials.

- Cherry picking data: When only the data that supports the conclusion is selected, results could be skewed and inconsistent

- Misconstrued results: Much like with clickbait headlines, articles may provide misconstrued or misunderstood results in order to create an enticing story.

- Unsubstantiated conclusions: Be wary of conclusions framed by speculative language that require further evidence to be proven.

- Lack of peer review: With no peer review, scientific articles are far less reputable and may not be reliable. 153 studies have been published on the new coronavirus. 92 were not peer reviewed.

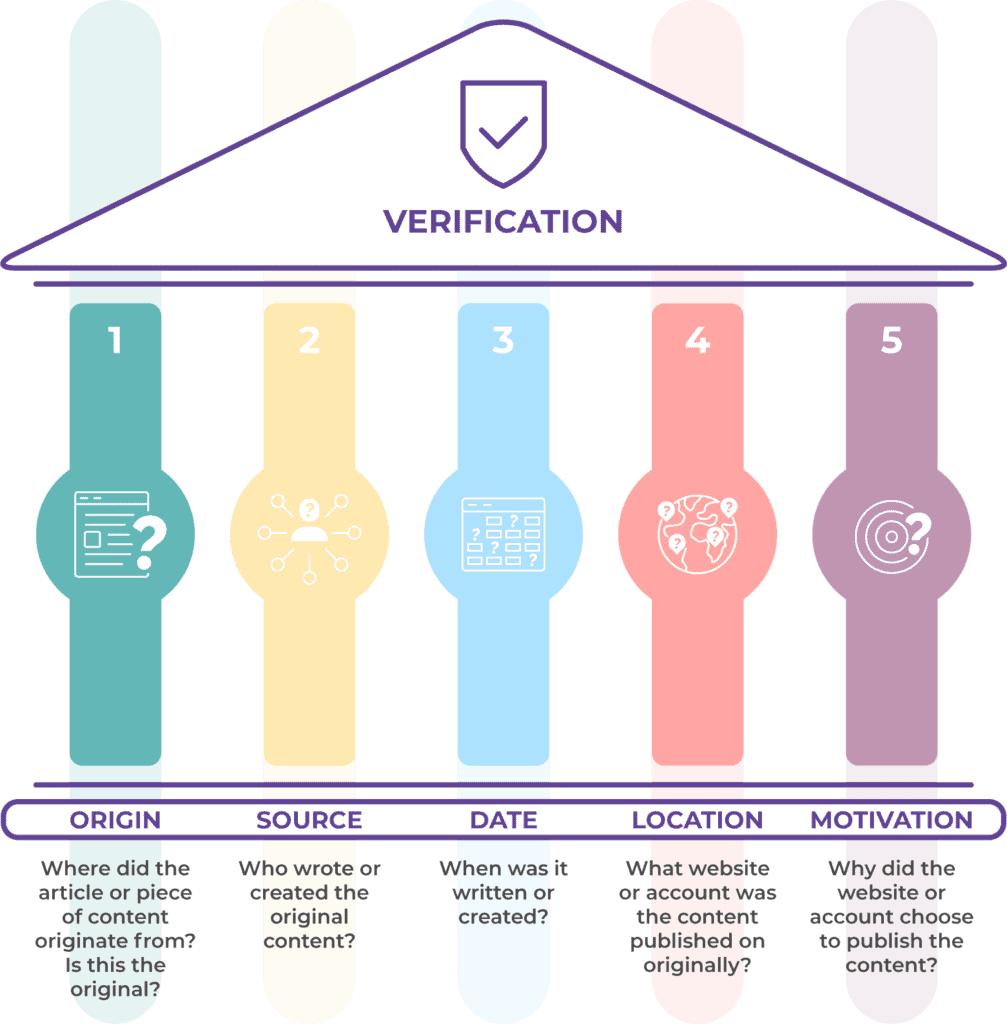

The Five Pillars of Verification

If you want your content to be as accurate and as persuasive as possible, it’s a good idea to learn how to verify content. The five pillars of verifications are:

Origin

If you are trying to find the first version of a meme or suspicious claim, before it made it into the mainstream, it is sometimes worth searching in these spaces:

- Check Reddit: You can use the native search bar, or Reddit monitoring tool like TrackReddit.com.

- 4chansearch.com allows you to search 4chan and 4chan archive sites.

- Gab.com is an alt-Twitter platform where many users who have been suspended have migrated.

- Discord channels, Facebook groups and WhatsApp groups are more difficult to find and search but may be worth the effort for deeper dives.

Source

- Contact: contact the person, either by calling or private messaging them.

- Question: ask the person questions, if they are not genuine, they may be vague about the facts.

- Permission: if the person does not have the right to let you use the content you are enquiring about; they will not be keen to undergo formal permissions.

Date

Finding the correct date for when the content was written or created can help in identifying the reliability, truthfulness and correctness of the content.

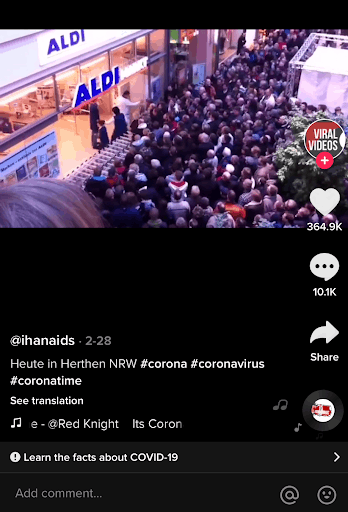

Case study During Covid-19 there have been cases around the world of hoarding, whereby individuals are buying large and unnecessary amounts of produce from the supermarkets in order to stock up. Photos and videos began circulating that appeared to show this hoarding. This screenshot from a video on TikTok was viewed over 4 million times, and appears to show huge crowds outside a supermarket, with the caption implying it was due to corona. Bellingcat were able to prove the video was old, and not related to the current Covid-19 crisis, instead dating back to an Aldi sale in 2011. |

Location

Finding where the content was originally posted is also important in order to identify how reliable the content is.

Case study This image went viral, apparently showing doctors and nurses that had died in Italy. However, this image is taken from a popular television show, Grey’s Anatomy. You can discover this through using a reverse image search, as AFP Fact Check did. |

Motivation

You can also ask yourself why the information was shared:

- Is it clear that the authors wanted to sell the audience something?

- Inform them?

- Entertain them?

- Persuade them of a point of view?

- Teach them?

- Is the information presented impartially and objectively?

- Are there obvious biases: political, religious, institutional?

All of these questions should help you judge how to deal with the information.

Verifying Images

Ten tips to ask yourself when fact-checking photos:

- Can you find when the picture was first used?

- What is the context the picture was used in?

- Who is in the picture? Do they fit in? What clothes are they wearing? Is it the right style for the country the picture was allegedly taken in?

- What is the weather like in the photo? If the photo is recent, is it the right season for that country?

- Look at any writing in the photo, like road signs and shopfronts. Is it in the correct language?

- Check for inconsistent lighting or slight variations in light or colour in the photo. If some objects seem brighter or duller than others, there is a chance they could have been added or digitally manipulated.

- If there are distortions along the edges of people or objects, the picture has probably been poorly manipulated.

- Check, check and check again, before you tweet or post.

- If someone posts something that is old or “fake”, politely let them know.

- Be part of the solution! Follow these tips so you do not contribute to “fake” news.

Exercise: Take this quiz to see how well you can spot a fake photo. How Well Can You Spot Fake Photos?

Exercise: Practice your image verification skills using the TinEye Reverse Image Search tool to discover hidden details and manipulation on digital images. This image surfaced on many blogs, social media sites and media. Is it real or fake? Start with practicing on the manipulated image already provided. Make sure to check out the most interesting data that Tin Eye provides you: Meta Data tool, Geo Tags tool, Date or Location. Try with some other pictures you suspect might be fake.

Tools for Verifying Images

- Google reverse image search

- FotoForensics provides budding researchers and professional investigators access to cutting-edge tools for digital photo forensics.

- Exifdata

- Exiftool

- MetaData2Go

- Forensically (picture verification):

- Tin Eye Image Verification

Tools for Verifying sources

- TweetBeaver (assists in verifying a particular user by looking at the relationship between users, a user’s timeline or specific account data)

- Botchecker for Twitter

Tools for Verifying Video

- YouTube Data Viewer (This tool shows users the upload time of a video after they copy and paste the link into the search bar. With this website, users can also view thumbnails and a link to reverse image search the thumbnails):