Introduction to Disinformation

Key notions

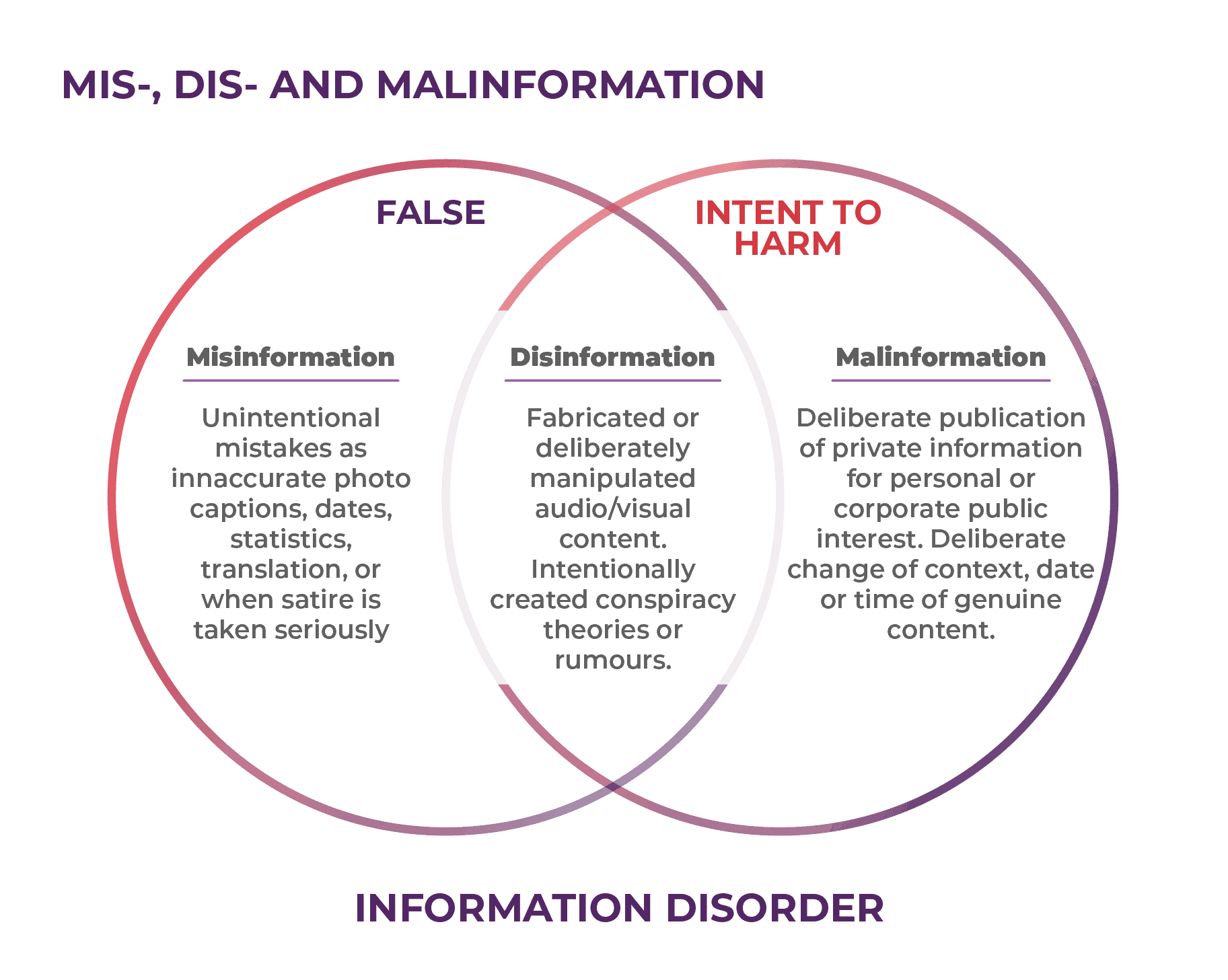

Not all false information can be classified as disinformation. So, it is important to understand the difference between dis-, mis-, and malinformation.

- Disinformation is intended to do harm, it is designed to manipulate. These stories are often entirely made up or use deliberately manipulated content.

- Misinformation is unintentional. It can be a mistake by a journalist, or someone who shares gossip. It can still be harmful, but there is no intent to do harm.

- Malinformation is intended to do harm, but uses factual information. This can be done by exposing someone’s private information or pictures, or by using content out of context.

Definition Quiz

The 7 common forms of information disorder

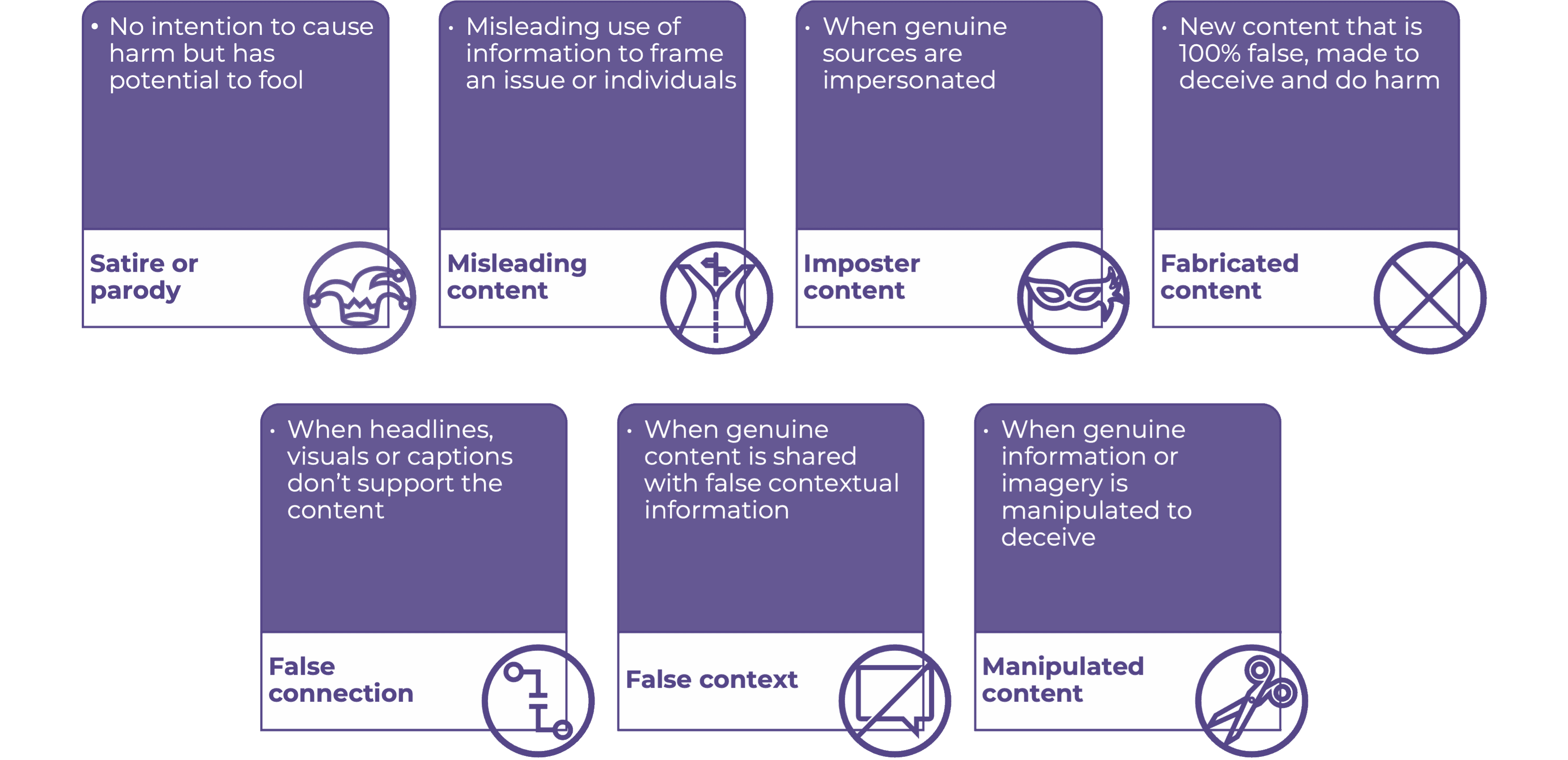

There are seven distinct types of problematic content that sit within our information ecosystem. They sit on a scale that loosely measures the intent to deceive.

1. Satire or parody

Satire is a sign of a healthy democracy. A good satirist will shine a light on an uncomfortable truth and exaggerate it in a way that leaves the audience in no doubt about what’s true and what’s not. The audience recognizes the truth, recognizes the exaggeration and therefore recognizes the joke.

The problem is that satire can be used strategically to spread rumors and conspiracies. If challenged, it can just be shrugged off that it was never meant to be taken seriously. “It was just a joke” can become an excuse for spreading misleading information.

2. False connection

Beware of clickbait. It is when you see a headline or photo that’s designed to make you want to click it, but when you click through the content is of little value or interest. We call this ‘false connection’ — sensational language used to drive clicks, which then falls short for the reader when they get to the site.

A study at Columbia University found that 59% of all the links shared on Twitter were not opened first, meaning that people shared them without reading past the headline. Clickbait techniques won’t stop – media organisations need the clicks! But as readers, we need to be wary of them as they often use polarizing and emotive language to drive traffic, which can cause deeper challenges.

3. Misleading content

What counts as ‘misleading’ can be hard to define. It comes down to context and nuance: How much of a quote has been omitted? Has the data been skewed? Has the way a photo been cropped changed the meaning of the image? This complexity is why we’re such a long way from having artificial intelligence flag this type of content. Computers understand true and false, but ‘misleading’ is a grey area. This is why human judgement is often needed to flag content as well.

4. Imposter content

Our brains are always looking for mental shortcuts to help us understand information. Seeing a brand or person that we already know is a very powerful shortcut. We trust what we know and give it credibility. Imposter content is false or misleading content that claims to be from established figures, brands, organizations or journalists.

5. False context

This term is used to describe content that is genuine, but has been warped and reframed in dangerous ways. All it takes is finding an image, video or old news story, and reshare it to fit a new narrative.

6. Manipulated content

Manipulated content is when something genuine is altered. Here content is not completely made-up or fabricated, but manipulated to change the narrative. This is most often done to photographs and images. It relies on the fact that most of us merely glance at images while scrolling on phone screens, so the content doesn’t have to be sophisticated or perfect. All it has to do is fit a narrative and be good enough to ‘look real’ in the two or three seconds it takes for people to choose whether to share it or not.

7. Fabricated content

Fabricated content is anything that is 100% false. This is the end of the spectrum and the only content we can really call ‘fake’. Staged videos, made up websites and completely fabricated documents would all fall into this category.

Some of this is what we call ‘synthetic media’ or ‘deepfakes’. Synthetic media is a catch-all term for fabricated media produced using AI. Through synthesizing or combining different elements of existing video or audio, AI can relatively easily create ‘new’ content in which individuals appear to say or do things that never happened.

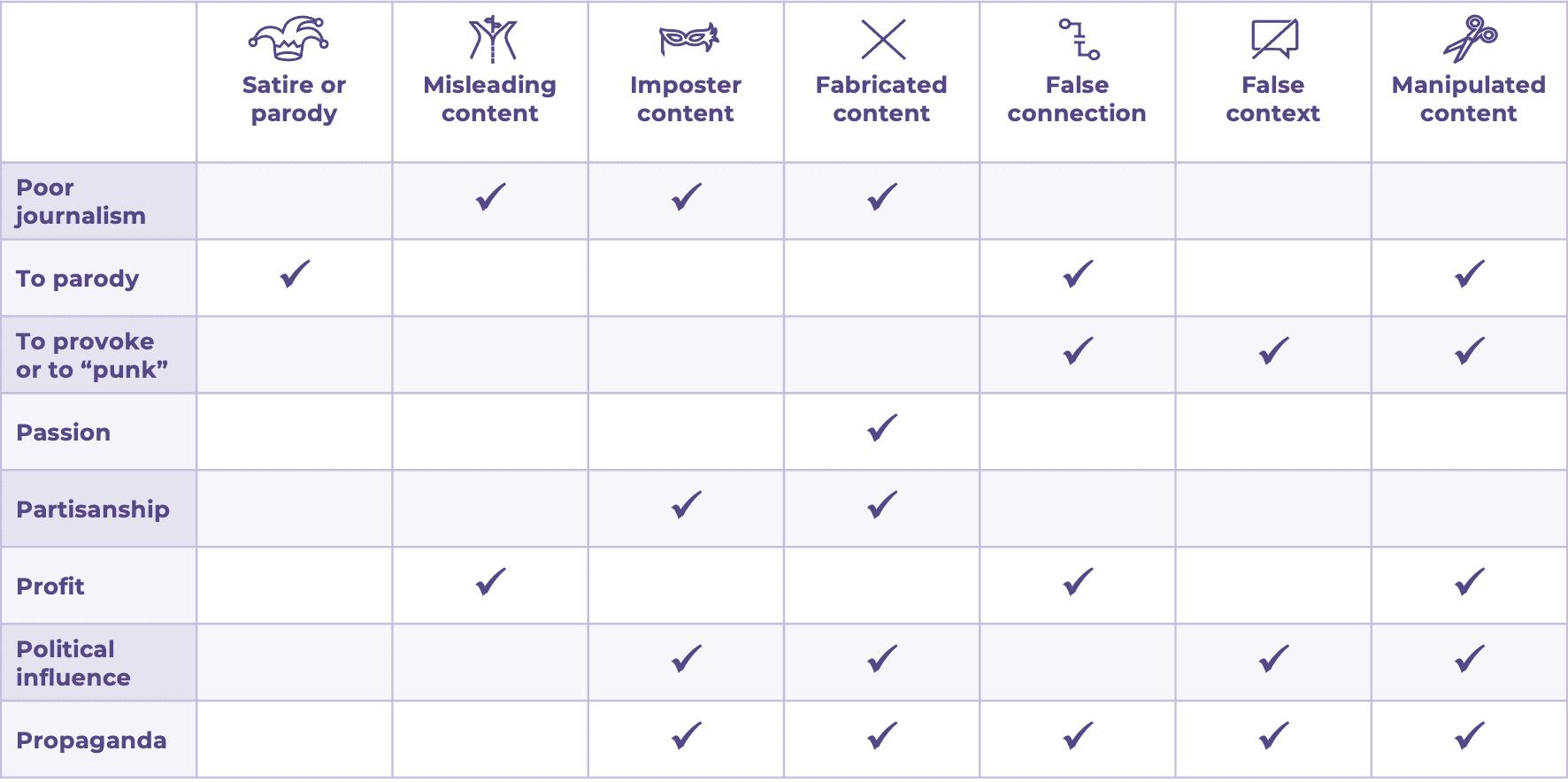

Journalists, or individuals, may have different motivations for engaging in the common forms of information disorder. This table shows 8 different types of motivations, the 8 ‘P’s: Poor Journalism, Parody, to Provoke or ‘Punk’, Passion, Partisanship, Profit, Political Influence or Power, and Propaganda. These can be mapped against the forms in order to see distinct patterns in terms of the types of content created for specific purposes.

The 8 Ps

Journalists, or individuals, may have different motivations for engaging in the common forms of information disorder that we just discussed. This table shows 8 different types of motivations, the 8 ‘P’s: Poor Journalism, Parody, to Provoke or ‘Punk’, Passion, Partisanship, Profit, Political Influence or Power, and Propaganda. These can be mapped against the forms in order to to see distinct patterns in terms of the types of content created for specific purposes.