Mobilisation Tactics

What is Mobilisation?

Before the early 2000’s “social media” meant a group of people watching a movie together or interacting around a video game in the arcade. Today the term includes digital platforms where millions of people share ideas, likes and dislikes, form communities and respond to phenomena around the globe. We have formed a complex digital society that demonstrates the connectedness of the individual to the world they live in and their thoughts of that world through the conversations they have.

During the millions of interactions of online communities, data and evidence for advocacy is collected. Sometimes this data has the power to change norms, values, beliefs and even the ways laws and policies are enforced in a country.

Mobilisation is a set of organised activities to create an enabling environment for national and international political and policy change. Public mobilisation seeks to engage public audiences with key issues to inspire widespread support, motivate people to take action, and harness and demonstrate popular support. In doing this we harness public pressure for change. Mobilisation can also be seen as a mainstreaming process.

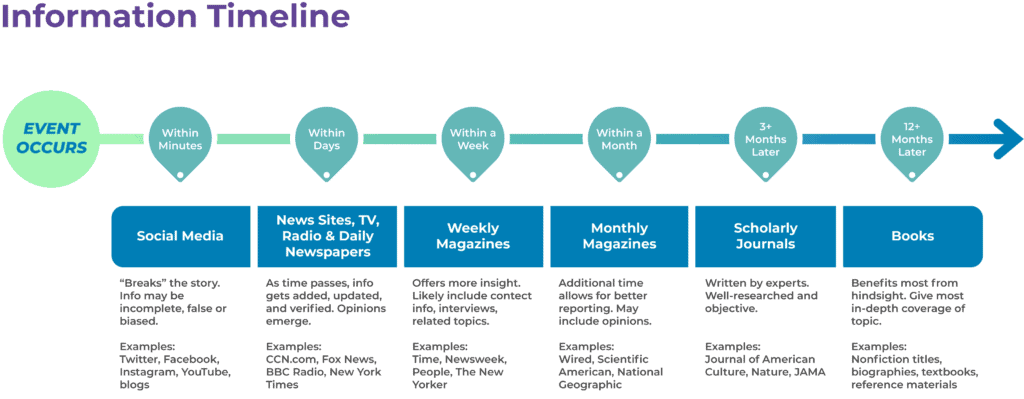

How the Information Cycle Works

Typically, an event happens, this could be the sharing on social media, for instance, of a report or opinion, etc. Then there is online discussion, usually within minutes. The value of the online discussion is important as the bigger the discussion, the more likes, shares, comments etc, the information gets, in a short amount of time, the more likely the information will be seen.

If there are many responses to a piece of content social media algorithms will identify this information as important and highlight this in their curation of stories in their feeds.

At this point the information shared may or may not be verified and can be incomplete, false or biased. If conversations online have created a buzz around a certain topic or information and algorithms have determined that this is a trending or important topic, it usually will be picked up by the local or international media (depending on the topic and size of the discussion). This then will be amplified through traditional channels, discussions and other means of disseminating information.

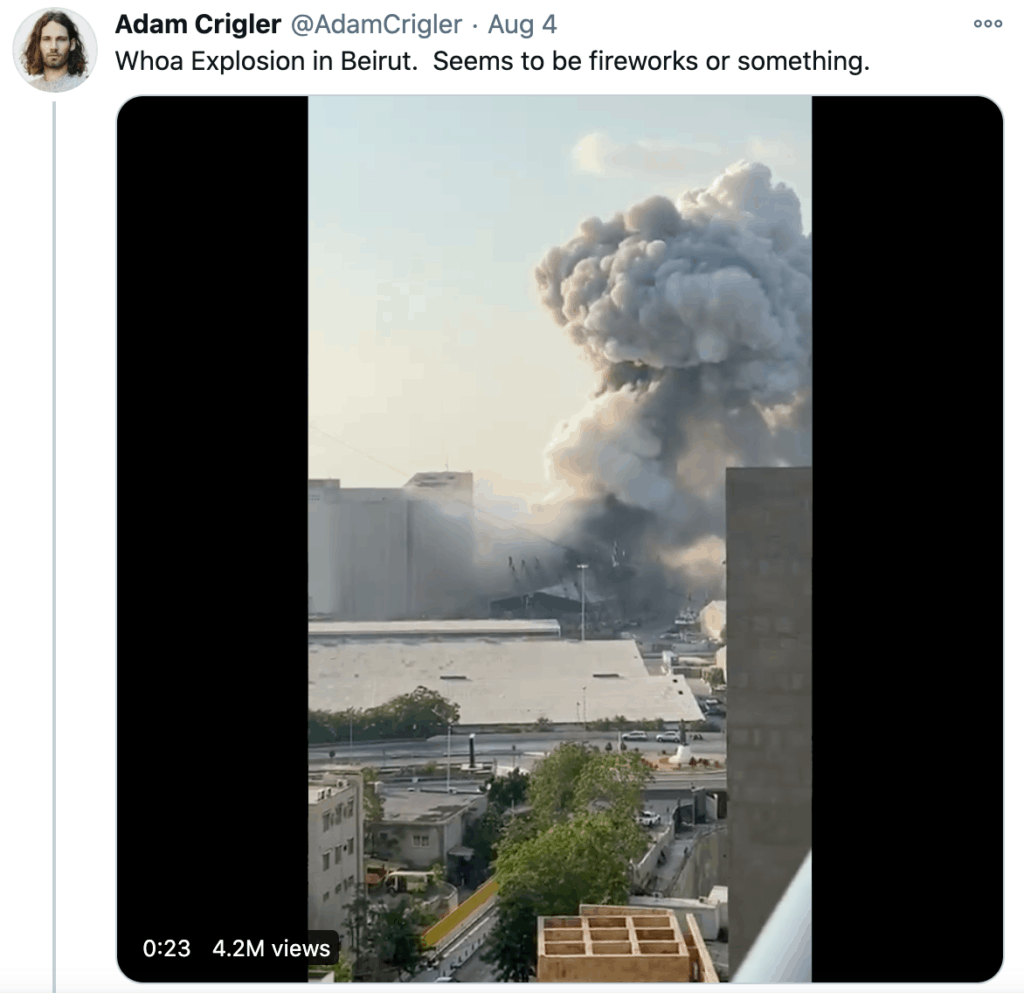

Below: An example of mobilisation in 3 tweets. After these tweets, local and international media were soon to pick up the story to report it. Important to note, that in these tweets it is evident that misinformation is spread as facts are not clear. In early reports, even in the mainstream media, it was reported that a fireworks factory had exploded. Some reported that a bomb had gone off linking it to conjecture that the government wanted to deflect attention from the outcome of a high profile court case.

During the days that followed the event, the news media continued to cover the events amplifying the narrative into the mainstream and international audiences.

Exercise: Based on the case study below, can you identify where mobilisation took place?

| CASE STUDY Benbere was launched in Mali in May 2018. The platform aims to reflect the voices of a highly fragmented country. There is a striking lack of knowledge among young Malians about their peers in the different regions of North, South and Centre as well as of the different ethnicities and traditions. Benbere enables young Malians to understand each other better. Benbere produces a lot of testimonials (mainly on video). An example of this was when the Benbere team decided to raise the issue on the silence that surrounds rape and sexual violence in Mali on their Facebook page with the post: Do you think victims are best protected by denouncing the perpetrators or by keeping quiet? The post was read by around 14,300 people and received just over 600 comments – more than any other Benbere post has ever had before. Amidst all those comments, there was one in particular that caught the team’s attention: “I was raped when I was 12, and my family did nothing, except for humiliating me. To them I was the shame of the family… I was only 12. My family never denounced the perpetrator. God is going to make him pay one day, the man that raped me.” After contacting her, the young woman decided to share her story. In the video, the now 26-year old woman describes what she went through and how her family beat her instead of supporting her because they thought she was to blame for what had happened: “My aunt went to get a whip to hit me, instead of taking me to the hospital. When I was 12, no one helped me even though my clothes were torn and I had blood running down to my feet.” In less than two weeks, the video was seen around 360,000 times, and it received hundreds of comments, most of which were very supportive. Another girl has since turned to Benbere to confide her experience of rape. As part of the 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence (GBV) campaign, Benbere published a series of articles under the hashtag #MaliSansVBG and organised offline events including performances by artists and actors popular with young Malians. Gender-Based Violence is a serious problem in Mali but remains largely taboo. The Benbere team aimed to raise awareness and start a broader conversation around the issue. Offline activities included a theatre piece highlighting the harmful consequences of GBV. In total around 1,000 people attended the performances and in a survey at the end of each show, 90% of the young people interviewed said they learned a lot about GBV. As a result of the campaign, Benbere was invited to the World Bank office in Mali, for their awareness day against GBV and took part in a panel with the representative of the Ministry of Economy and Finance and the evaluator of the national programme to combat GBV. |

Mobilisation through Social Media

a. Mobilisation through Organic Promotion and Virality

Social media is a great channel to instantly share valuable information, oppose disinformation and to implement positive narratives that go beyond the reactive approaches to achieve our desired impact. The mechanics of social media and the ultimate goal in mobilisation is reach. Reach is the number of people who are exposed to information.

Social media uses algorithms to prioritise content. Algorithms control the ordering and presentation of posts, so users see what is most relevant to them. This relevance is usually based on friends, family and acquaintances. Social media platforms use the same logic in serving content to their users. Friends, peers, family are regarded more credible to the audience and therefore platforms will prioritise content from these sources. In 2018, Facebook changed its algorithm to prioritise friends, families and the groups that users joined as more relevant and therefore more visible in users’ timelines.

Social media is designed in a way to keep our dopamine levels high. This works in the same way drugs work on the brain. A user posts something, they then get validation which hikes up their dopamine levels. They then continue to return to their posts to check on additional comments and validation. This cycle of dopamine release becomes addictive to users. This ensures that behavior is reinforced and ensures habit formation. Users are presented with more notifications than before, because it was observed that receiving notifications drives users to return more frequently. More relevant content also ensures more usage time. This too happens when users comment, they want others to respond or their comment to be validated in some way.

Content is said to have “virality” if organically a post is shared, liked and commented on in a short period after posting (usually within 60 minutes). Virality is the tendency of an image, video, or piece of information to be circulated rapidly and widely from one Internet user to another.

b. Mobilisation through Paid Promotion

As identified in the organic promotion section above, algorithms have a tendency to prioritise the family, friends and groups of the user. This makes starting new conversations, exposing new ideas and challenging existing narratives of some user segments, difficult.

Filter bubbles, echo chambers and bias are important considerations in the amplification of ideas. Bias is a tendency to prefer one person or thing to another, and to favour that person or thing. An echo chamber is a situation where certain ideas, beliefs or data points are reinforced through repetition of a closed system that does not allow for the free movement of alternative or competing ideas or concepts. A filter bubble is the intellectual isolation that can occur when websites make use of algorithms to selectively assume the information a user would want to see, and then give information to the user according to this assumption. Websites make these assumptions based on the information related to the user, such as former click behavior, browsing history, search history and location. For that reason, the websites are more likely to present only information that will abide by the user’s past activity. A filter bubble, therefore, can cause users to get significantly less contact with contradicting viewpoints, causing the user to become intellectually isolated.

In order to break through echo chambers and filter bubbles that are naturally caused by social media and websites, it’s necessary to use paid advertising in order to reach audiences.

Paid content can do 3 things that organic content cannot. They can be worthwhile considering if:

- Your aim is to reach a specific vulnerable group that will be affected without the information.

- Reaching the public to raise awareness. Especially to educate an indifferent population or one in which media bias exists.

- Spreading an alternate narrative or discourse to break through an echo chamber.

c. Mobilisation through the Promoting of Ideas within Broader Online Channels

Mobilisation through special interest groups online takes the form of more targeted campaigns. These can be to target a specific online group and influence their behavior for instance, targeting political parties to surface youth issues ahead of an election through online campaigns, charters, petitions and cyberstorms (emails, messages, comments across their social and online media).

Mobilisation online connects different communities, or different channels and includes them in the information dissemination. Mobilisation online could take the form of:

- Cross channel promotion and content sharing, for example from Facebook to WhatsApp, Instagram and Twitter. These are usually linked through hashtags or other trackable identifiers.

- Repackaging or repurposing content/ insights online into blog posts or other content, this could take the form of posters, graphics, infographics, video, animations or creating listicles or interactives.

- Hashtag sharing, where hashtags are popularized and used consistently.

- Swarming: through which communities work together to comment, promote, cross promote or popularize content. Swarming may also be done by mass emailing targeted individuals (lawmakers and politicians) to express concern or dissatisfaction. In many countries if more than a certain threshold of people express dissatisfaction for a law or policy then it needs to go to discussion.

- Influencer marketing: whereby online personalities with large communities of followers share information or promote hashtags/ information.

- Search Engine Marketing: Amplification of ideas can also be done through promoting posts for more reach and visibility.

- Additional examples could be: develop a charter, facilitate an Online petition, data gathering / data visualisation hackathons, developing and distributing surveys, distributing electronic action alerts (SMS/WhatsApp), facilitating challenges (like ALS Ice bucket challenge and TikTok challenges), online crowdsourcing expertise, hosting live online interviews, discussion groups and open forums on research or findings , hosting virtual talks; Webinars and workshops , facilitating Online protests, Banner Changes and email campaigns.

Mobilisation through Radio and Television

Radio and TV interviews are a crucial part of what any NGO does. Even if you don’t have to do them yourself, you should ensure that you understand the basics and that everyone in your organisation who may have to be interviewed has had some basic training in how to look and act. The wrong way to approach an interview is to think “I’ll see what questions they ask, then answer them”. The right way is to think “What is the best use I can make of this opportunity, what is the most important thing I want that audience to hear”. This “most important thing” is usually known as the Key Message.

Try to avoid anything that sounds like an advertising slogan or mindless cheerleading. Back it up with some evidence – usually numbers, and what is often called the “soundbite”. It lasts between 10 and 45 seconds, depending on the style of the broadcaster; as a rule of thumb, aim for about 20-25 seconds. When journalists are going through a recorded interview, they are looking for a quote to include in their package which both sums up your argument and is clear and interesting. It’s in your interest to give them a good “soundbite”, something that best represents your Key Message. This needs preparation.

To get to your message, use a “bridging” technique. This involves acknowledging the journalist’s question briefly, then using a linguistic device or phrase which carries you on to what you want to talk about. These devices, or “bridges”, are phrases like “our chief concern at present”, “what we are focusing on”, or simply “however” or “but”. Try to think what questions you are likely to be asked and write down as many ready-made answers as you can. Most difficult questions can be anticipated ahead of time. This will increase your accuracy, and make you look more professional. Try to pass on to your positive messaging as soon as you can, but do not try to minimise serious issues such as deaths as though they are not important.

If you don’t want to answer a question, (or you cannot answer it for legal or other legitimate reasons) you should use a “close-down” technique. This can be a ready-made phrase such as “It is too soon to speculate” or “We cannot speak for the ministry”. This makes it clear that you will not talk about a subject at all. If you simply don’t know the answer to a question, it is best to simply say so; promise to find out the information and deliver it later. Do not use repeated close downs if you can avoid it, only one or two in a whole interview.

Here are some practical tips for an interview:

- Avoid the phrase “no comment” because people think it means the organization is guilty and trying to hide something

- Present information clearly by avoiding jargon or technical terms.

- Appear pleasant on camera by avoiding nervous habits that people interpret as deception. A spokesperson needs to have strong eye contact, limited disfluencies such as “uhms” or “uhs”, and avoid distracting nervous gestures such as fidgeting

- Brief all potential spokespersons on the key message points the organization is trying to convey to stakeholders.

Mobilisation through Press Conferences and Events

A press conference is a staged public relations event in which an organisation or individual presents information to the news media. It serves as a focus for your agenda and when used with Twitter or webcast can become a live “news event” in its own right, available to the general public too. Communications officers use press conferences to draw media attention to a potential story. They are typically used for political campaigns, safety and health emergencies and promotional purposes, such as the launch of a new product or campaign. They can be a waste of time and money – and damage your credibility with your journalist contacts, if the story is not newsworthy or they are poorly organised or carried out.

Here are some tips to help you as you plan a press conference:

- Decide if it is necessary. If you could do it another, cheaper way, consider whether that would be better. Decide exactly what your story is. The best way to do this is to draft your Press Release – that will be the key message of your press conference. Senior executives sometimes have to be dissuaded from demanding a press conference when there is insufficient “news” to announce to justify one.

- Selecting an appropriate venue to hold your press conference is crucial. Ask yourself the following:

- Have you got enough space?

- Is there parking for TV trucks and journalists?

- Is there adequate seating?

- Is there a stage or a podium?

- Have you got enough power points for people to plug into?

- Is there audio-visual support?

- Is there space for TV cameras, and radio mics inside?

- Is it close enough to where journalists have their offices?

- Decide who you are going to invite. Your journalists contact list is a good starting point, but this is also an opportunity to invite a few more people on the off-chance they may be interested. Avoid sending mass email invitations – it looks unprofessional and unfocused. There are lots of methods to contact journalists – some traditional such as mailing, some creative ways such as sending an invite on a bar of chocolate. Make sure you have some idea of who is coming by following up the initial invitation with a reminder.

- Make sure the speakers are good at dealing with the media. Don’t have more than two speakers to avoid confusing the audience. Tell the speakers not to speak for more than about 10 minutes at a time, and to keep focused on the key messages. Go over the material with them beforehand so they don’t introduce anything inappropriate. You can anticipate a lot of the questions in advance so the speakers should have ready, clear answers to those questions. Visual aids can be powerful – but don’t let them overwhelm the conference and turn it into a lecture.

- You will need a “moderator” or “facilitator” to introduce your speakers and make the question and answer session run smoothly. Often that person will be the communications lead in the team. It’s an important job. He or she needs to prevent more aggressive members of the audience from dominating the questioning, protect nervous speakers from bullying questioners, keep the conference on the main topic, make sure each question is clearly understood (some accents can be hard for visiting speakers to decipher) and ensure you keep to the allotted time.

- Put together “press kits” in advance. These should include as a minimum the press release, any other background material on your organisation, paper and a pen. Free gifts such as mugs and hats can be put in too, but avoid expensive or showy goods which may suggest you are trying to bribe people (even if you are not!). You could also prepare name identifiers on stiff card to place in front of the speakers so that the audience is always aware who is speaking.

- Get to the venue at least an hour before the start to set up an “accreditation” table – so you can monitor who is present and who has yet to turn up – and to check the technical and physical logistics of the room and other facilities. Don’t forget the bathrooms, which may need to be labeled! A good press office has a “primary school teacher” kit with pens, scissors, tape, paper, clips, etc. just in case something goes wrong and you have to improvise.

Provide someone to greet people as they arrive and show them where to set up – this is particularly important for technical teams. It is not necessary to provide food during a press conference, but coffee, tea and water will always be acceptable, and inexpensive to provide. After all, you want the journalists to be in a good mood! In some developing countries, poorly-paid journalists will welcome something a bit more substantial. Stick to the timetable, and don’t let it last for more than an hour, including the question and answer session. Ensure that people identify themselves when they ask a question, and the moderator is prepared to repeat the question both to give the speakers time to think and to allow everyone in the room to hear.

Thank everyone for coming, and make sure you follow up quickly afterwards if you have said you will provide extra information. You should also offer private interviews after the press conference if you care to give TV and radio journalists the chance to ask more targeted questions.

- You could also do tweeting “live” from the press conference. That would help spread the “buzz” beyond the journalist community and put pressure on them to issue a report. You cannot do this while moderating, so you might need to dedicate a member of staff to do it. Not everyone will approve of your speaker or your campaign. So, while you want to be as open as possible, make sure that hostile groups do not infiltrate your press conference to disrupt it and prevent the speaker from speaking. Only bona fide journalists and other invited guests should be allowed in.

Mobilisation through Offline Action

There are several ways that important information can be amplified through physical offline action. It’s good to note, that it’s also important to realize that all the activities in this section can be further mainstreamed through media attention. Media can amplify the message even more. In the previous section we explored the press conference and work with journalists, these should not be abandoned in mobilisation efforts on the ground.

Here are examples of mobilisation tactics in the offline space:

- Petitions: Internet petitions; action cards; giant petitions -anything where numbers matter. When specialists or VIPs put their names to these types of initiatives it can help to mobilise public support.

- Mass communications: arts events: posters, billboards, radio, or TV advertising; organising pop concerts, festivals or other events that engage large numbers of people; or PR activity with celebrities, art exhibitions or auctions.

- Letter writing: lots of people writing to decision makers or other influential individuals; you can help by providing sample letters or postcards with talking points. You can also provide pre-written postcards.

- Use the system: use of parliamentary procedures, legal cases, Freedom of Information requests or judicial review; creative use of government statistics and announcements; use of obscure procedures; get ordinary people involved in government consultations.

- Disinvestment: the use of a concerted economic boycotts to pressure a government, industry or company towards a change in policy.

- Youth led and Youth-centred campaigns and advocacy are variations on the above themes: debating clubs (inviting politicians); youth forums; youth parliaments; speakers’ tours; children’s choirs, bands, theatre groups performing in halls or in the streets; essay/poetry/drawing/painting competitions; marches or vigils with visual props/symbols; exhibitions, showings of photos or videos taken by young people; peer education.

- Public hearings: mobilise the community to participate in public hearings in front of local officials, government, civil society leaders and the media. People from the community are able to voice their concerns about issues and have their voices heard directly.

- Mass rallies and marches: Mass rallies and marches can be effective tools and, although not a common tactic for all organisations. They can harness the energy of the community and direct it at a target that can make change happen, whether a government, public institution or corporation. There is a long and proud tradition of non-violent rallies and marches. These kinds of activities are usually more forthrightly political in tone and action than an awareness-raising event. Because the political quality of a March or rally is more acute, these kinds of activities must be carefully planned, with special attention paid to ensuring sufficient and well-trained marshals to guarantee participant safety –particularly important when young people are involved.

- Debates: Debates can function to present different viewpoints on an issue and include decision makers and young people.