Storytelling

Storytelling is central to our experience as humans. It defines the world around us and gives meaning to seemingly random events. In order for us to comprehend phenomena, primitive humans created myths and legends (stories) to make sense of them. As our storytelling became more advanced, stories developed moral lessons, which helped shape attitudes in societies. Our very existence is interpreted as a story through a sequence of events we tell people we meet.

The story theory in this toolbox was first explored by Aristotle (300 BC) in his work “Poetics” a meditation on the structuring of classical Greek Tragedy and Comedy. In the 19th century, the theories were expanded by German playwright and novelist Gustav Freytag. The techniques of storytelling are not new. Humans have been sharing stories as long as we have been communicating.

Story Definition

There are many interpretations of story and storytelling. Many equate ‘story’ with ‘fiction’. Story is not fiction. Fiction (or drama) is a type of story. Robert McKee, considered the greatest screenwriting teacher, defines story as:

“An imperfect protagonist, who in an attempt to improve his/her life, sets off on a quest towards a physical goal but along the way is met by a series of physical obstacles of ever increasing difficulty. Ultimately the character overcomes their central flaw (imperfection) thus can achieve the goal of their quest.” McKee, R. 1997:24. Story, Structure, Substance and the Principles of Screenwriting. HarperCollins. Los Angeles.

Story includes events (things that happen in a logical progression) and characters (actions that happen to an imperfect hero) forcing the character to learn something (and therefore share a lesson with the audience). A simple definition for our purposes could be:

“Something that happens (events) to someone (character) that teaches us something (moral premise).”

Just the Facts Please, Then 5W’s and an H

Traditional journalism and communication bases its structure on the 5 Ws and the H (What, where, who, when, why, how?). It concerns itself with facts and structures these facts into what is termed “the inverted pyramid”. The inverted pyramid style originated through a technological limitation. Telegrams were used to relay important information over great distances, due to the unpredictability of the line connection, important facts needed to be transmitted first. It would always be ‘Headline” then the essential information. The basic facts were included in the structure according to diminishing importance (the downward pointing triangle), in case communication was cut. Similarly, publishers of newspapers could simply make the story shorter by cutting it from the bottom up, to any point after a lead, in order to make the story fit the space available.

The inverted triangle started as a print structure but as radio popularity grew, newspaper journalists moved to newsrooms in radio, and simply applied the structure they were familiar with to news broadcasts. Later, as television developed in the 1950’s, and radio journalists moved to TV, the inverted pyramid structure was taken up in television, too. In the 2000’s similar migrations of journalists happened to the online space and social media. However, for the first time, audiences were able to choose what they wanted to consume, instead of being force-fed through the broadcast media. The result was dwindling profits of news-based organizations and favourable uptake in media that was relevant, emotionally engaging and had a story quality to it.

Persuasion is Learning with Emotion

In this toolbox, we are presenting you with the ‘Persuasive Storytelling Methodology’. This is simply a method to make content that reaches an audience through story with lasting impact. The ‘persuasion’ is learning (adopting new knowledge skills or attitudes) through logically structuring information and providing emotion that is relevant to the audience we wish to reach.

Research continues to show the link between story and fact retention; facts without story are easily forgotten, while stories are remembered accurately for a longer period of time. The story also provides a framework for remembering key facts and information and therefore most people can repeat the story with accuracy. A good example of this is Islam’s Holy book the Qur’an. The book survives because the stories in it were passed down orally and accurately remembered by groups of devotees.

The basic assumption of the persuasive storytelling methodology is that one needs both logical information and emotion to be able to bring your target audience new Knowledge, Skills or Attitudes. Great stories carry emotion and they teach us something.

Harnessing Emotion through Storytelling

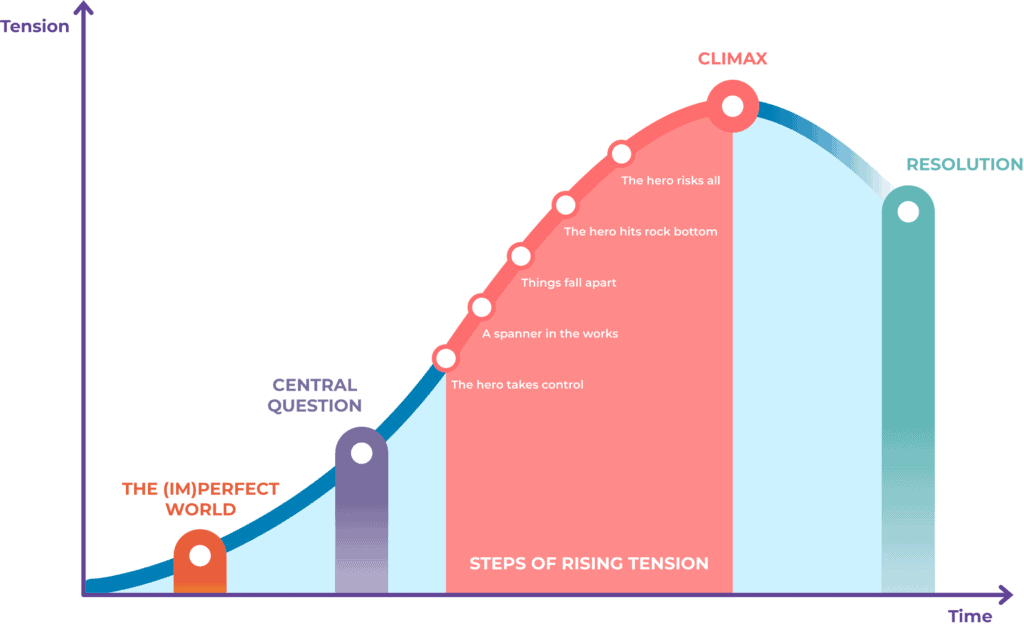

There are 8 essential elements to building a story. Humans enjoy stories that follow the basic structure and we have become very good at applying this structure to our stories. The elements build tension, meaning that we want to find out what happens next. In the age of the ‘attention economy’ where it is no longer a given that people will pay attention, storytelling is vital to ensure the audience is pulled to the end of the story in an engaging way. While the story elements seem like a Hollywood formula, they can easily be applied to campaigns.

The 8 essential elements are:

- Tension and time

- The (im)perfect world

- The central question

- Steps of rising tension

- Climax

- Resolution

- Symbols

- Universal Truth

Each of these are explored in detail below. The following is a graph that illustrates the ‘arc of tension’ a visualization of the eight essential elements:

Tension and Time

Tension is the feeling an audience has of trying to figure out what happens next. A story requires the tension to build, so our desire to find a solution to the problem posed in the story gets greater and greater as the story progresses. As humans are problem-solving creatures, we want to be confronted with a problem we want to solve, we make an assumption about how the problem will be solved and then we see if our assumption is correct. This tension must rise during the story. We do not like stories that go no-where or stories that have very low tension.

Time relates to story time. A story may happen in a few minutes or may take decades. What is important is that the period is chosen for maximum tension. Can the story best be told chronologically? Or is it more suspenseful to use flashbacks?

The (Im)perfect World

All great stories start by showing us a perfect world. Even if the world we enter into as the audience is not a perfect world, for the people in the story it is. This perfect world ends when the central question is introduced.

The Central Question

The central question is a yes-or-no question. It is: ‘Will the Hero win the heart of the girl?’ Once the perfect world has been introduced, we need to be confronted by a problem or quest that the hero must solve. This question will draw the audience to try and find the answer through the story. The answer will be given in the climax of the story. Until the climax, the viewer must ask him- or herself what could happen next?

Rising Tension

Rising tension is created by events that the character responds to. Humans like twists and turns and stories that have challenges that the hero faces. Good story presents lots of obstacles. We want to see the hero try and fail, try and fail and fail and try again until they succeed. Without obstacles in the way (the steps of rising tension) we feel cheated and we disengage from the story.

For example:

- The hero takes control

- A spanner in the works

- Things fall apart

- The hero hits rock bottom

- The hero risks all

Climax

The climax is the answering of the central question. It is the moment in the story in which the character is rewarded or punished for adopting new behaviours; it is a moment of irreversible change. In this part of the story we learn the answer to the question we have been waiting for in the story.

Resolution

A resolution is the consequence of the story. Usually the hero is rewarded, and the enemy punished. Order is restored, and a new perfect world is established. The most common ending in fiction is ‘and they lived happily ever after…’ to conclude the world of the narrative. This is created to give the audience a concluding emotion. A resolution shows the reward the character has earned and demonstrates a positive or negative emotion in the audience for what has been learnt.

Symbol

A symbol is not a structural component of a story. Rather it is a story device. A symbol in story is more than a symbol in language. A story symbol has specific requirements and is defined differently than something that is ‘symbolic’.

A symbol is a name, a place, an object or anything that:

- Has meaning beyond itself

- The meaning of the symbol changes from the beginning of the story to the end

- The symbol is culturally understood

Universal Truth

A story is “something that happens to someone that teaches us something”. The universal truth is the moral premise of the story, something we learn as an audience. It is usually attitudinal and based on an emotional shift. The universal truth is the deeper meaning of the story, it is what the audience is left with at the conclusion and is usually a strong argument and an attitudinal lesson.

Exercise: Write a story based on fact. Select a current affairs news story, ideally from the news of today. It would be a good idea to review how many different versions of the story exist on other sites or in other papers. Based on the news story, write your own version according to the story-arc. Include the eight elements; 1. Tension and time, 2. The (im)perfect world, 3. The central question, 4. Steps of rising tension, 5. Climax, 6. Resolution, 7. Symbols and, 8. Universal Truth.